|

Purpose-driven organisations perform better and have more engaged employees, but staff are particularly prone to burnout. Read on to discover why, and what you can do to support your purpose and your team.

Photo by Joice Kelly on Unsplash

Purpose-driven organisations naturally inspire commitment and passion among their people, who are driven not only by salary and benefits, but by their desire to make a difference.

Often this is highly beneficial, with purpose-driven organisations performing better and having more satisfied employees. One survey found that purpose-driven organisations achieved 30% higher levels of innovation and 40% higher retention rates. Another survey found that 25% of British managers would take a pay cut to work for a purpose-driven organisation. The commitment shown by employees to purpose-driven organisations is impressive, but it should be handled with care – because people who are passionate about their jobs often find it hard to stop, and that commitment can then quickly turn into over-commitment and burnout. In other words, purpose doesn’t remove stress (and may actually heighten it). What is burnout?

In May 2019, theWHO officially recognised burnout as an ‘occupational phenomenon’, though the term has been used since the 1970s, when it was first used to describe air traffic controllers who, despite their extensive training and generally high performance, began to make mistakes.

The WHO definition defines burnout as “resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed”, characterised by “feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion, increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and reduced professional efficacy.” The results can be devastating for both individuals and organisations. Burned out employees are 2.6 times more likely than others to be looking for a new job, 63% more likely to take sick days and 23% more likely to visit A&E. It’s also incredibly common. Some studies put burnout rates at 60% or higher in some professions, with medics, teachers and finance professionals especially vulnerable. But burnout isn’t necessarily linked solely to particularly stressful work: one study found that 13% of the Dutch working population suffer from it. What causes burnout?

The effects of burnout can be severe, leading to people becoming completely unable to work. And they often creep up slowly, without either the affected person or their employer realising what’s happening.

One model of burnout identifies 12 stages of burnout. Stage 1 is simply the compulsion to prove oneself, which hits those who are most engaged the hardest, followed by stage 2, working hard. As burnout progresses, the negative effects begin to get stronger, including disrupted sleep and eating patterns, rejection of hobbies and social life, emptiness and depression. Stage 12 is complete mental and physical collapse. It’s those first two stages of burnout: compulsion to prove oneself, and working hard, that are the clue to why burnout can develop in purpose-driven organisations, even those that generally demonstrate care towards their employees. If the people who show the most commitment to their jobs are most likely to suffer from burnout, and those who work in purpose-driven organisations are more likely to be committed to their jobs, then it’s easy to see how a belief in the purpose of an organisation can translate from hard work to burnout. Medical staff, especially doctors, are particularly prone to burnout, with as many as 1 in 3 suffering from it at any one time. The role demands a commitment to work as a meaningful cause, rather than simply a way of earning a salary. That provides fulfilment, but can tip over into severe stress and burnout, especially when combined with the pressure of responsibility. Some individuals may also be more prone to burnout than others, with those who are more inclined to perfectionism, high expectations and the need to serve others being particularly prone. It might well be that people who fit this profile are also those who are especially likely to work for purpose-driven organisations outside the medical sphere. Since the day, several people had told them, “I am so grateful that I work for an organisation that cares about my wellbeing.” What’s the cure for burnout?

While it’s clear that some people are more likely to fall prey to burnout than others, it is important not to fall into the trap of blaming individuals for burning out. Burnout is not an individual problem but an organisational one.

Some organisations have tried to solve the burnout problem by investing in wellness programmes, such as providing on-site yoga classes or space for meditation. But the evidence is that wellness programmes do nothing to tackle burnout and may even have the opposite effect. Staff who see money being spent on wellness, rather than on the practical problems that are causing them stress, may well end up feeling resentful. They might also feel blamed: if they miss their lunchtime yoga class, are they then responsible for their own stress? People who burn out tend to feel unsupported and that their workload is unmanageable. They might feel that their work doesn’t have the impact they expected, but feel that raising this would be disloyal to the purpose of the organisation. Rather than questioning processes or workloads, they begin to believe that the problem must lie with them. One study that interviewed employees in purpose-driven organisations about burnout found that they often felt frustrated that they weren’t able to achieve what they wanted to, but were instead struggling with unmanageable workloads. They spoke of feeling “drained” and that there was “too much work, too few people”. One said that “often success is about the activity and not about the impact. Success is about a meeting, not about what it means; [the activity is] celebrated more than the outcome.” All this is compounded by the lack of separation between work and home, leaving most of us few opportunities to truly switch off from work. This is especially true for those working from home, but even those in the office will often expect to have to work into the evening and at weekends as a matter of course. In a purpose-driven organisation, it’s particularly hard to resist the pressure to work long hours. Take a collective break in the woods

The answer could be to take a collective break. Burnout is an isolating experience, made worse by poor communication.

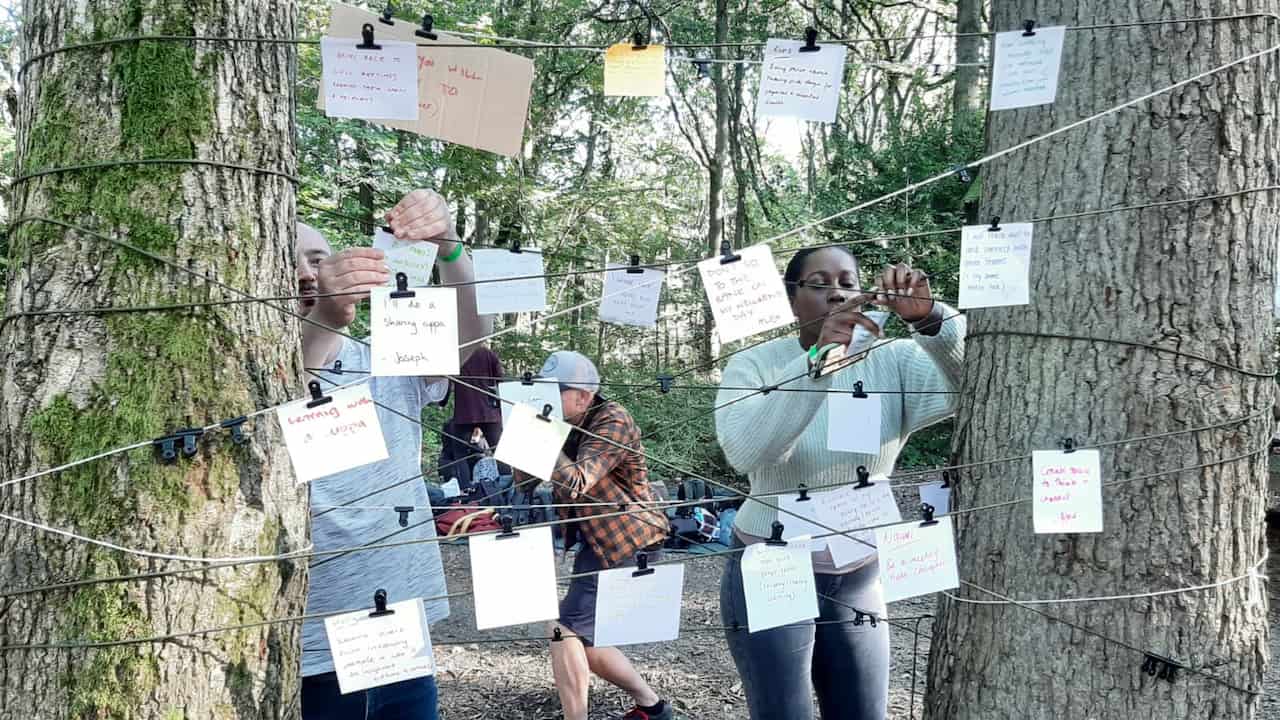

A day together, in nature, is an opportunity to get completely away from work and digital distractions, and to talk about how you can change your culture to reduce stress and burnout and increase wellbeing. With phones handed in or switched off at the beginning of the day, and opportunities to experience how nature provides a natural stress cure, you’ll finally have the space you need to breathe, talk and understand each other. You’ll leave with an action plan that everyone agrees on. For example, we worked with one purpose-driven and people-first client recently who had formed a wellbeing working group during the pandemic because people had become stressed and isolated while working from home. The wellbeing group wanted to ensure that people took time off from a busy schedule, and to find a way to come together to talk about the uncertainty of the current times. We designed a day for 40 of their people in self-contained woods in South London focussing on the question (agreed in advance) of how to stay connected and maintain well-being as they adapted to a new flexible way of working. Based around the fire with dappled sunlight falling through the leaves, the group re-built the connections with each other that they had lost from 18 months in front of screens. In small groups they enjoyed learned from activities including sensory awareness with trees, foraging for health, making fire without matches, and working together to build a shelter. You could see the impact it had on people.

What became apparent in the afternoon group workshop was that both as an organisation and individually they take on too much, and how could they stop doing that?

Sharing, listening, working together to generate ideas they spoke about what they do well, and came up with various practical actions and commitments for some things to stop, and other steps they could take to start to work on these challenges. It’s that last bit that’s crucial. The collective commitment you may have to your purpose can make it difficult to talk about the stress you feel when you don’t have the impact you want. The more open you are able to be as a team, the easier it is to talk. A couple of weeks later one of the leaders told us in the debrief how good it was to find an opportunity to do things differently and start to build a new culture. Since the day, several people had told them, “I am so grateful that I work for an organisation that cares about my wellbeing.”

Would you like to reduce stress and burnout in your team and prioritise wellbeing, while increasing performance? Get in touch to discuss how School of the Wild’s outdoor team programmes in Sussex and London can help.

Comments are closed.

|

Author & CuratorNigel Berman is the founder of School of the Wild. Archives

March 2024

|

Leaders |

About Us

Support |

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed